Where Data Tells the Story

© Voronoi 2025. All rights reserved.

“Sport is a symbol of hope and of peace, which are sadly in short supply in our world today,” Grandi, Vice-Chair of the Olympic Refuge Foundation, said on Friday, the official start date for the Paris 2024 Olympics. Speaking of the Olympics’ 36-strong refugee team, who are standing for over 120 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, he continued: “The refugee team is a beacon for people everywhere. These athletes show what can be achieved when talent is recognized and developed, and when people have opportunities to train and compete alongside the best. They are nothing short of an inspiration.”

There’s a lot to be said for the Olympics. They inspire and unite people around the world, promote diversity and provide important role models. At the same time, according to the International Olympic Committee, the games can help "promote elite and grassroots sport", improve infrastructure in a hosting city and can provide job opportunities, while developing a region's respective business and tourism industries.

But, on the other side of the coin, the competition raises concerns over security, overcrowding for locals, the environmental impacts and the costs of hosting. In recent weeks, as has been witnessed in the Olympic games before, there has even been “social cleansing”, as thousands of homeless people have been removed from the Paris region.

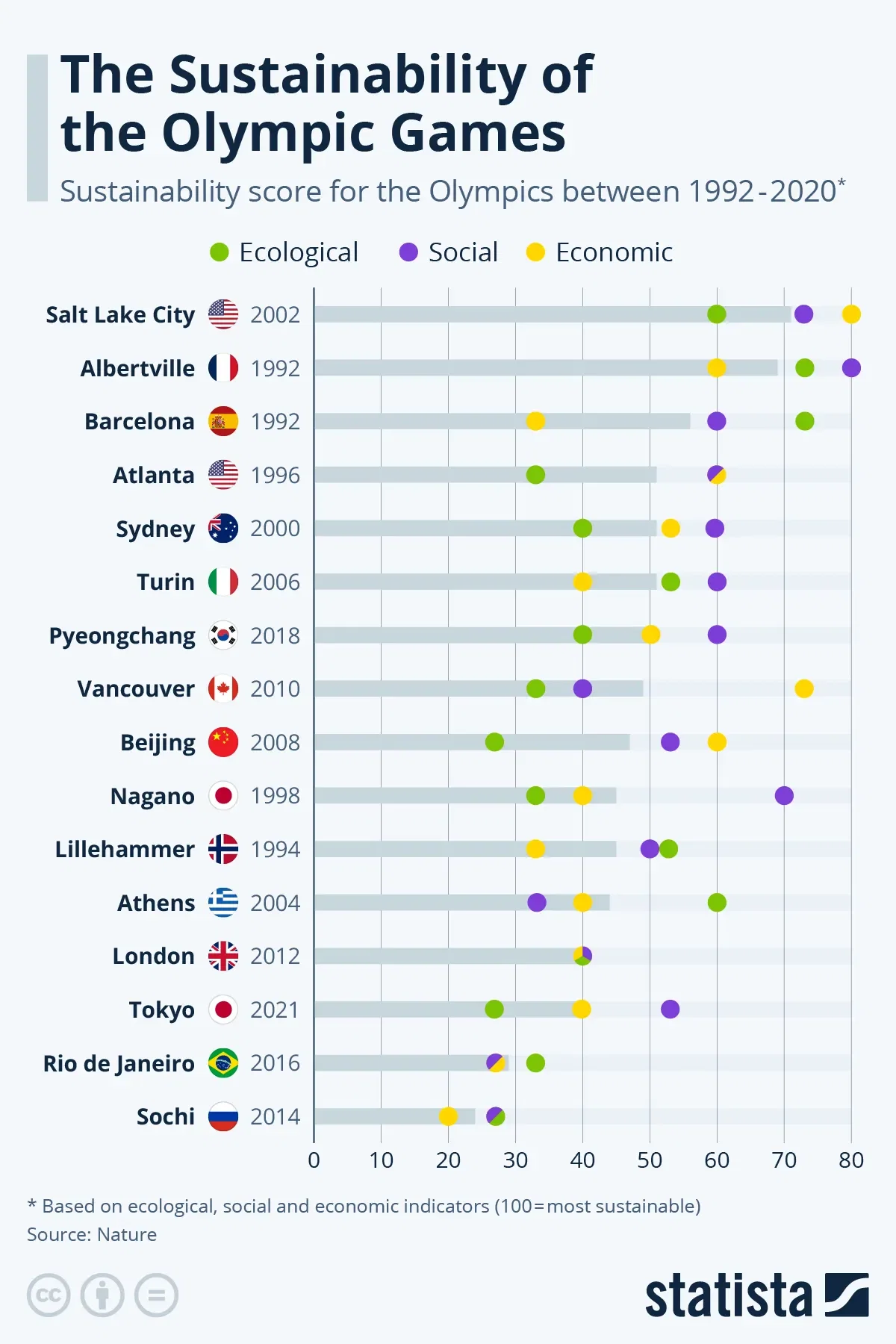

The following chart is based on a study published in the scientific journal Nature and compares the levels of sustainability for the Olympic Games between 1992 and 2020, based on three indicators which cover ecological, social and economic factors.

According to the study, the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics in the United States, the 1992 Albertville French Winter Olympics and Spain’s Barcelona Summer Olympics in 1992 performed best of the analyzed group, with a mean score of 71, 69 and 56, respectively. The top scores in Salt Lake City and Albertville are somewhat unexpected, according to the report, with the former having been “overshadowed by a bribery scandal and the events of 11 September the year before”. However, Salt Lake City’s Games also saw positive after-use of venues and had overrun costs to a lesser degree than some other editions of the Games.

In the case of the Albertville Olympics, which had been criticized for environmental damage caused by the construction of new sports venues, these Games still performed fairly well due to having a smaller ecological and material footprint because it was a smaller event. None of the analyzed games, however, managed to achieve a mean score above 75, which would have categorized them as sustainable.

At the other end of the spectrum comes Russia's Sochi Winter Olympics of 2014, with an average across the three indicators of just 24 out of a possible 100, and only 20 points on the economic subcategory. Rio de Janeiro’s 2016 Summer Olympics also performed poorly with a mean score of 29 as well as the lowest score (along with Sochi) in the social category. According to the report, this low score was due to high numbers of residents having been displaced for Olympics-related development in the run-up to the competition and the new sports venues having been “poorly used” after the event, while cost overruns were also high.