Where Data Tells the Story

© Voronoi 2025. All rights reserved.

Vietnam is currently struggling with the fallout from Typhoon Yagi, which hit the north of the country over the weekend, causing at least 21 deaths as well as landslides, floods and the destruction of homes. Yagi also killed at least 20 in the Philippines and four in Southern China, while causing a million people to flee.

With 8,000 houses reported damaged and tens of thousands of people at least temporarily displaced, the human cost of typhoons is high. But there is also an economic cost that lingers long after the typhoon season is over and that is connected to the many citizens and businesses repairing or rebuilding structures damaged in the weather events – with collective costs often in the billions of dollars.

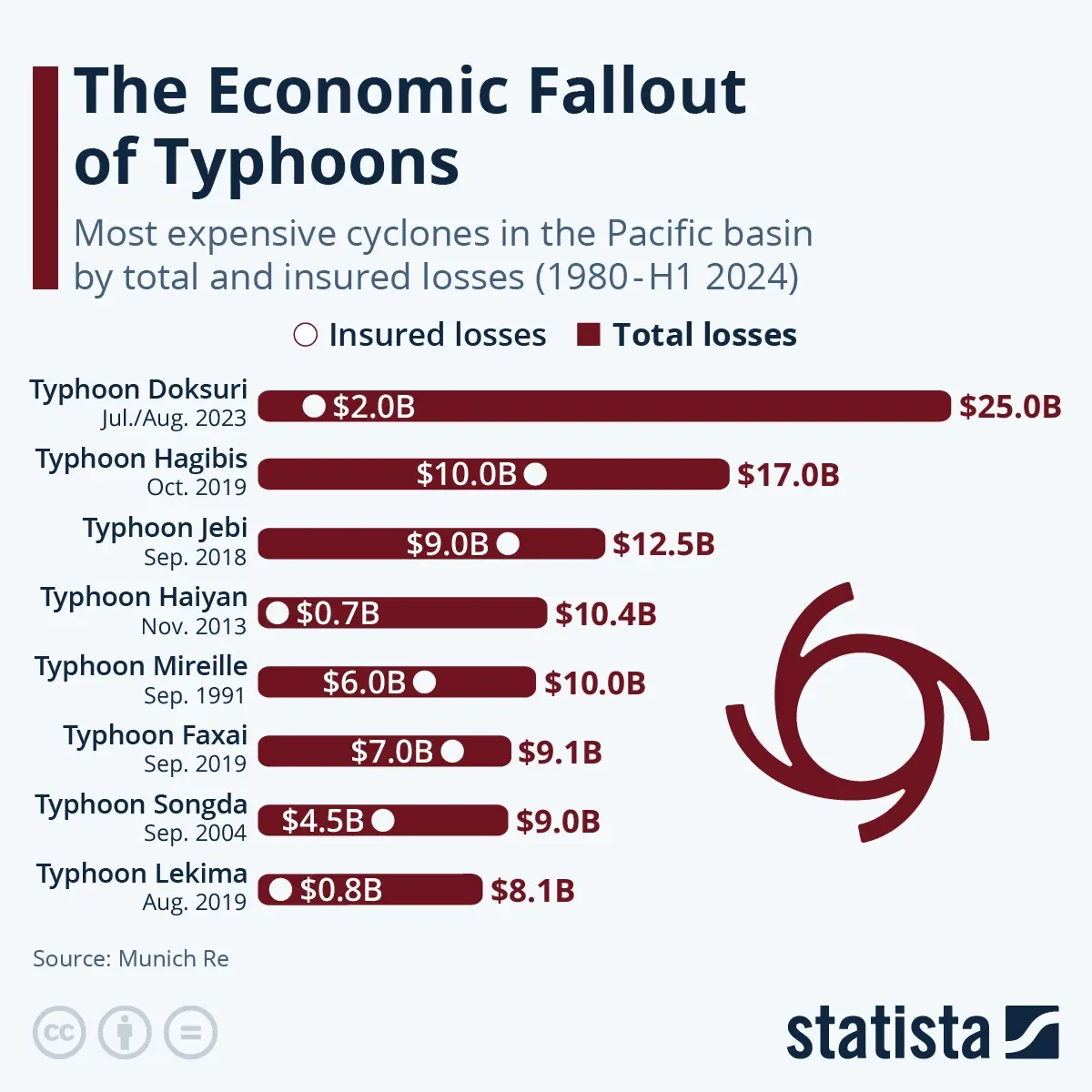

On the Pacific coast, this cost was the highest after Typhoon Doksuri, which hit Mainland China, Taiwan, Vietnam and the Philippines in July and August of 2023 and caused the death of 137 people. Insurer Munich Re estimates the total monetary losses for the event at $25 billion. Since 1980, Typhoon Hagibis (October 2019), Typhoon Jebi (September 2018), Typhoon Haiyan (November 2013), Typhoon Mireille (September 1991) have also caused losses of US$10 billion or more. While Hagibis crossed Japan, Russia and Alaska and Haiyan also hit the Phillipines, China, Taiwan and Vietnam, Jebi and Mireille wreaked havoc on Japan. As visible in the data, the insurance levels for storms hitting Japan are significantly higher than those of storms hitting the Philippines or China (Typhoons Lekima, Fitow).

In the ranking of the eight costliest typhoons, five occurred since 2018, in line with scientists' predictions of natural disasters becoming stronger and more frequent because of climate change. The most devastating year was 2019, when Typhoons Hagibis, Faxai and Lekima caused combined damages of more than $34 billion in Asia. 2020 was more subdued when it comes to Pacific storms. Indian Ocean cyclone Amphan, however, caused major damages of $14 billion in India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Thailand that year. In the case of South Asian countries, insurance levels are even lower than in Southeast Asia and China, according to Munich Re.