Where Data Tells the Story

© Voronoi 2026. All rights reserved.

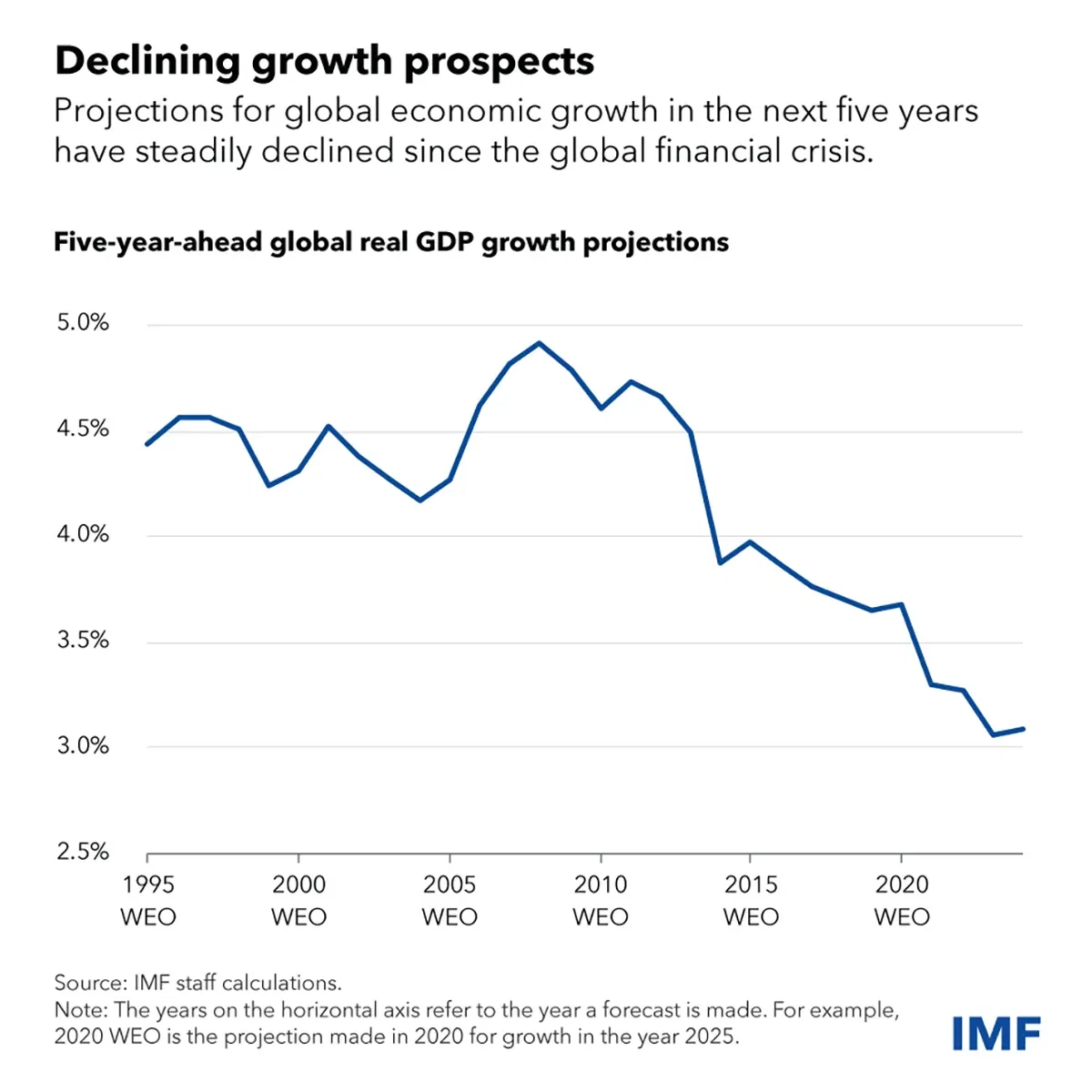

The world economy faces a sobering reality. The global growth rate—stripped of cyclical ups and downs—has slowed steadily since the 2008-09 global financial crisis. Without policy intervention and leveraging emerging technologies, the stronger growth rates of the past are unlikely to return.

Faced with several headwinds, future growth prospects have also soured. Global growth will slow to just above 3 percent by 2029, according to five-year ahead projections in our latest World Economic Outlook. Our analysis shows that growth could drop by about a percentage point below the pre-pandemic (2000-19) average by the end of the decade. This threatens to reverse improvements to living standards, and the unevenness of the slowdown between richer and poorer nations could limit the prospects for global income convergence.

A persistent low-growth scenario, combined with high interest rates, could put debt sustainability at risk—restricting the government’s capacity to counter economic slowdowns and invest in social welfare or environmental initiatives. Moreover, expectations of weak growth could discourage investment in capital and technologies, possibly deepening the slowdown. All this is exacerbated by strong headwinds from geoeconomic fragmentation, and harmful unilateral trade and industrial policies.

However, our latest analysis shows that there’s hope. A variety of policies—from improving labor and capital allocation across firms to tackling labor shortages caused by aging populations in major economies—could collectively rekindle medium-term growth.

The key drivers of economic growth include labor, capital, and how efficiently these two resources are used, a concept known as total factor productivity. Between these three factors, more than half of the growth decline since the crisis was driven by a deceleration in TFP growth. TFP increases with technological advances and improved resource allocation, allowing labor and capital to move toward more productive firms.

Resource allocation is crucial for growth, our analysis shows. Yet, in recent years, increasingly inefficient distribution of resources across firms has dragged down TFP and, with it, global growth. Much of this rising misallocation stems from persistent barriers, such as policies that favor or penalize some firms irrespective of their productivity, that prevent capital and labor from reaching the most productive companies. This limits their growth potential. If resource misallocation hadn’t worsened, TFP growth could have been 50 percent higher and the deceleration in growth would have been less severe.

Two additional factors have also slowed growth. Demographic pressures in major economies, where the proportion of working-age population is shrinking, have weighed on labor growth. Meanwhile, weak business investment has stunted capital formation.