Where Data Tells the Story

© Voronoi 2026. All rights reserved.

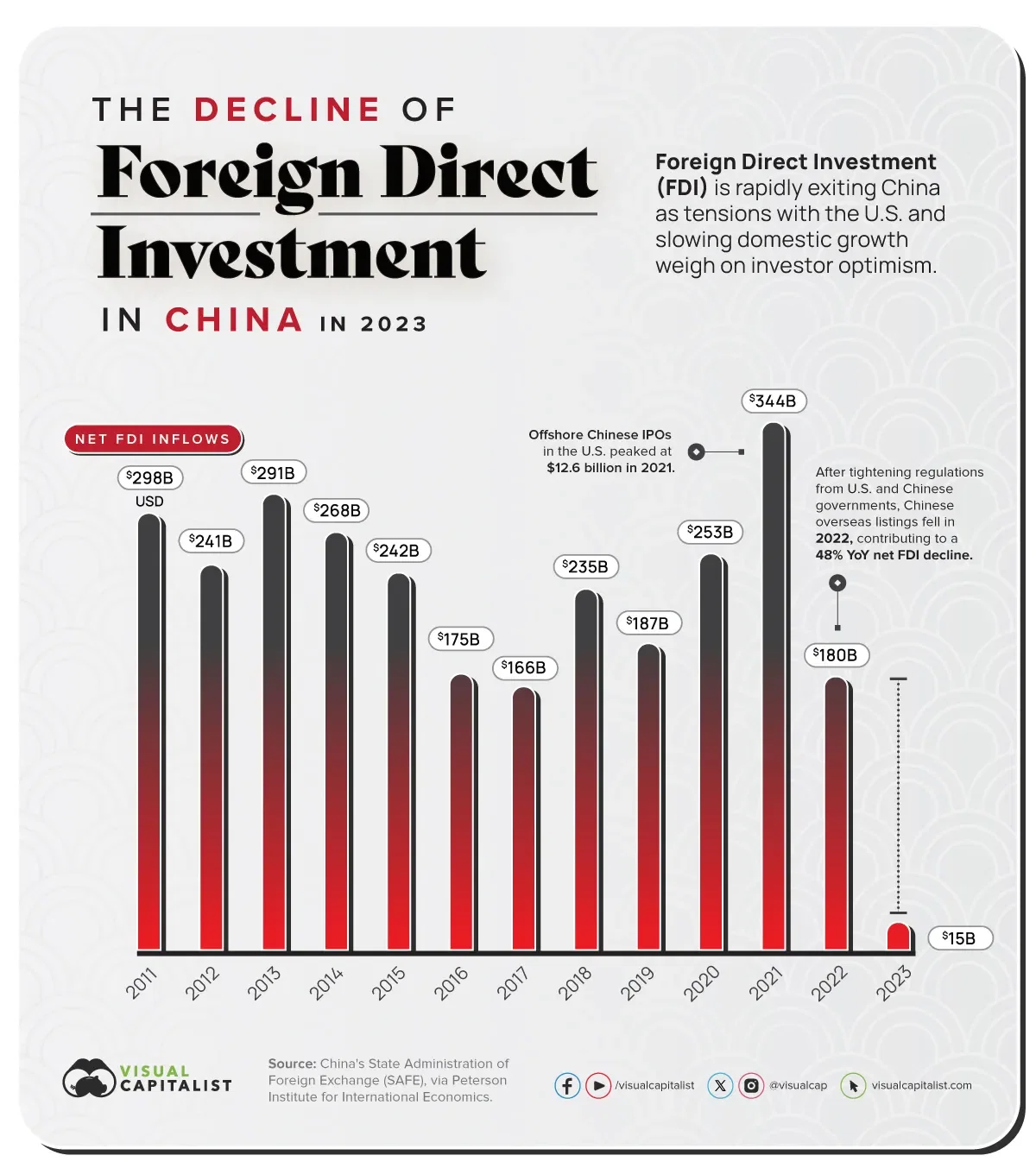

The Chinese economy has thrown up several red flags in 2023 and now foreign investors are losing confidence in the world’s second-largest economy.

Data accessed via the Peterson Institute for International Economics and sourced from China’s State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE) shows foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows have hit multi-year lows.

Context: FDI occurs when an investor in one country acquires significant and lasting financial interest in a foreign enterprise. This data includes the IPO value of Chinese companies in foreign markets.

Aside from a broadly slowing economy, the Peterson Institute’s analysis highlights other key reasons why FDI inflows have scaled back so dramatically this year.

Firstly, geopolitical tensions (in the form of an escalating chip war) between the U.S. and China are worrying foreign investors—many of them American-headquartered companies with a presence in China, holding investments in local companies.

Secondly, the closure of due diligence firms (which allow foreign investors to make informed decisions on Chinese companies) along with a new national security law aimed at restricting cross-border data flows have disincentivized foreign investors from betting big if they wanted to.

Meanwhile, huge spikes in FDI inflows between 2018 and 2021 indicate the success of Chinese companies listing on American securities exchanges, which SAFE includes in its data. However, crackdowns from both Chinese and U.S. securities regulators in 2022 turned the tap off briefly. Despite the restrictions being since removed, new listings have not bounced back.

The Peterson Institute’s comparison of gross and net FDI flows found a nearly $100 billion shortfall—which means foreign firms are selling their Chinese investments, adding yet another red flag for the economy. This slowdown is now having a ripple-effect across the region—for Japan, South Korea, and Thailand’s economies—whose export sectors rely on substantial Chinese demand. Nations in sub-saharan Africa will also feel the pinch as Chinese sovereign lending continues to fall, already past the lowest it’s been in two decades.

Meanwhile, on a broader scale, Chinese growth contributes to one-third of world economic growth, which means the global economy will miss growth projections made earlier this year—when economists had a more optimistic view of the world’s second-largest economy.